Alfred Fowler was born in Wilsden in 1868, his parents were Hiram and Eliza (nee Hill). Neither Hiram nor Eliza were literate and both signed their marriage certificate with a cross.

Alfred Fowler was born in Wilsden in 1868, his parents were Hiram and Eliza (nee Hill). Neither Hiram nor Eliza were literate and both signed their marriage certificate with a cross.

Hiram was a cotton warp dresser at Providence Mill and Alfred’s siblings all worked in the textile mills. The older children – Mary, Walker, Joseph and John – received their early education at the schoolroom attached to the Independent Chapel (now Trinity Church) in Wilsden and, though records do not exist, it seems probable that the following children, Walter, Alfred and William, also began their education there.

In 1872 Walter, the next older brother of Alfred, died from typhus fever. Their father Hiram subsequently suffered extreme depression and this may have been the catalyst for the family’s move to the Parkwood area of Keighley around 1876.

Alfred clearly showed early signs of being an excellent scholar as he was allowed to continue at school instead of entering the mills. He attended Eastwood Board School and won a scholarship to the Keighley Trade and Grammar School, where he flourished. At the extremely young age of 14 he was awarded a ‘Devonshire exhibition’ and won a place at the Normal School of Science (later the College of Science and now part of Imperial College, London) to read mechanics. Alfred is probably the youngest ever student to be admitted there.

In order to further fund his place at the college, Alfred became a ‘teacher in training’ and part-time ‘computer’ to Norman Lockyer who was Professor of Astrophysics and Head of the Solar Physics Laboratory attached to the college.

Alfred remained as assistant to Norman Lockyer, becoming the first ‘Demonstrator in Astronomical Physics’ in 1888, until Lockyer’s retirement in 1901.

During his time as assistant to Lockyer, he returned to Keighley to marry Isabella Orr, who was literally the girl-next-door when the Fowler family lived at Barrett Street in Parkwood.

Alfred’s work concentrated on Lockyer’s theories about the evolution of stars from nebulae. Lockyer had previously identified a new element which he called helium from the Greek word helios (sun).

Alfred focussed on identifying the spectra of stars. The light from the sun was photographed using a camera with a prismatic lens which split the light into various bands. The best opportunity for doing this was during an eclipse and they chased eclipses around the world with Alfred becoming expert at the photography and interpretation of the spectral bands. He also proved that areas of sunspots are cooler than the surrounding areas of the sun.

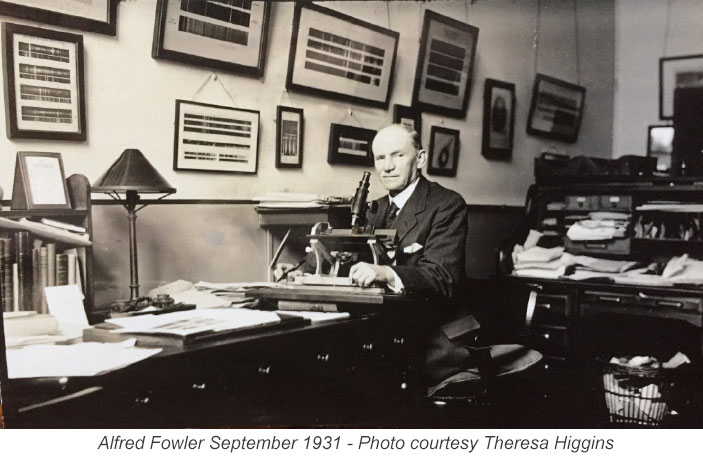

Following Norman Lockyer’s retirement, Alfred was appointed as Head of Astrophysics and started to step out from Lockyer’s shadow. In 1913 Alfred’s precise measurement of the spectral lines of hydrogen and helium caused Niels Bohr to revise his calculation of the Rydberg constant in his theory of atomic structure.

The realisation that the Rydberg constant can be accurately measured is a basis of atomic physics and from 1913 spectroscopy gained a sudden prominence.

In 1923 Alfred was one of two professors to be appointed to the Royal Society under a new endowment from the Yarrow Foundation. Alfred’s painstaking work on the identification and reproduction of celestial spectra and immense knowledge of the subject made him a world-leading authority and he was a collaborative and generous scientist.

Award after award was conferred on him: Fellow of the Royal Society in 1910, Valz prize (Paris Academy of Sciences) in 1913, Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1915, Draper Medal in 1920, Bruce medal in 1932, CBE in 1935.

We can only wonder at the remarkable path Alfred’s life took. Hiram and Eliza produced a son who must have seemed a cuckoo among his siblings. When Alfred was four he lost his closest brother and witnessed the effect on his father’s mental health. At just fourteen years old he went to London to live and work in an alien world where he was rubbing shoulders with the rich, privileged and educated. The day after Alfred’s eighteenth birthday his father took his own life. Perhaps then, it is not surprising that Alfred was so quiet and reserved, and that he threw himself into his work with such an all-consuming energy. Although he didn’t completely cut himself off from his past in Yorkshire (he and Isabella regularly visited her family in Keighley and Sutton-in-Craven), it would have been a strange collision of his two worlds.

Alfred and Isabella had two children, but only one grand-daughter and one great grand-daughter, who died tragically in a road accident aged 21. Perhaps the absence of a direct line from Alfred accounts in part for his lack of recognition nowadays, coupled with the man’s reserve and quiet manner.

Following Alfred’s death in June 1940, a former student and colleague wrote a fitting epitaph:

“Few men have seen so large a proportion of their work become a common possession of which not many remember the source. He was content that it should be so. His satisfaction came from the consciousness of work well and truly done, that would outlive his own name.”